Sometimes the past somehow catches up with us. Suddenly we’re face to face with someone who lived 1,000 years or more before our time. This often happens only through what archaeology and historical research bring out about an individual or group, but increasingly through the recreation of their actual faces through remains, DNA analysis and skilled sculptors. One of the persons from Swedish antiquity whose gaze we were actually able to meet is Estrid Sigfastsdotter.

Estrid lived in the 11th century in Broby Bro, a place which in modern times has been the subject of several archaeological excavations, not least in the search for more knowledge about the Jarlabanke family, to which Estrid, in her capacity as a paternal grandmother, became the female ancestor.

The daughter of the powerful and wealthy Sigfast, believed to have been one of Olof Skötkonung´s closest men, Estrid, was born to power and influence on the farm Snåttsta in Markim.

The absolute proximity to the king meant that Estrid grew up in the most distinguished families of her time when Sweden was slowly but surely moving from the ancient Asatron to the Christianity that had long been dominant on the continent.

Olof Skötkonung, who lived between the approximate years 980 and 1022, is the one who is considered to be the first Christian king in Sweden. His father, Erik Segersäll, was indeed baptized but returned to the old faith at the end of his life.

What made Sigrid special in ancient Swedish history, above all as a woman, are the traces she left behind, literally carved into stone.

It’s a sad fact, not least in Sweden, that the further back in history you go, the harder it becomes to find the women who, without a doubt, lived and died alongside the much more documented men. But Sigrid left her mark, even if we hadn’t had her recreated image, and perhaps she would have liked the somewhat defiant look she has been given. And one reason we see her is carved in runes.

Due to the number of rune stones, six in number, on which Estrid’s name appears on six stones, all located in the Swedish county of Uppland – itself the most runestone-dense region in Scandinavia – it can be concluded that she was an influential woman during her lifetime. Here she is mentioned as both mother, wife, and sister.

Estrid, who grew up with the mixture of both status and insecurity that it meant to be close to the king, is estimated to have been in her teens when she married Östen, with whom she had, among other things, the son Gag, who when he died was only 4-5 years old gave rise to the second rune stone, U 137, in which Estrid’s name is mentioned: ”Östen and Estrid raised the stone after Gag, their son.”

Even during her lifetime, Estrid was a woman who was most likely known far and wide. That we know it is again the rune stones erected on her behalf: the stone U 136 that is placed at Broby Bro, which can tell us that ”Estrid had stones erected for Osten, her husband, who went to Jerusalem and died away in Greece. ”

What Östen did in Greece, we will most likely never know. It has been supposed that, as a Christian, Östen was on a pilgrimage with Jerusalem as his goal. But that’s not something that can be absolutely certain. At this time, the Väringagardet was active, a bodyguard for the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople and mainly recruited from Sweden.

Another thing that has also been assumed is that when Östen died in Greece, Estrid remained at home, and perhaps that was the case; yet again: something we will never know for sure. But in 2005, an ancient church ledger was found in the Benedictine monastery in Reichnau on Lake Constance, a stop already for Viking-age pilgrims to Jerusalem. Therein are the names; Estrid and the East. It is impossible to know whether it is actually about Estrid and Östen, who are the subject of this entry. But perhaps she also left her name far beyond the country’s borders.

Estrid was about 30 years old when Östen died and became the single mother of several children, of whom only four sons are known to posterity. However, it is not a bold guess that she also had daughters. The names of the sons she had with Östen were Gag, as already mentioned, Ingefast, Östen and Sven.

Being a single mother a thousand years ago was not an option. Estrid soon remarried after Östen’s passing, and that to the widower Ingvar in Harg.

Also, in this marriage, several children were born. Still, only the sons’ names have survived into the present day: Sigvid, Ingvar and Jarlabanke. However, not the Jarlabanke who also survived into our time. We will return to him. But Estrid was the grandmother of the well-known Jarlabanke. As is so common in new family formations, Ingvar had his son, Ragnvald, with him.

The farm Harg was located in today’s Skånela parish. Estrid should have lived there for around 20 years before she became a widow again at 50. She then chose to return to the farm, Såsta, where she lived with Östen, to live with her son Ingefast and his family. Estrid Sigfastsdotter ended her life here, between 60 and 75 years old. She was buried at Östen’s burial mound, near where they once erected the runestone for their little son Gag.

Estrid’s story could have ended here, but it doesn’t. Instead, in 1995, it was a matter of road construction at Broby Bro, exactly where it is known with the help of old maps that Östen’s burial mound was once located.

During the work, three skeletons were found, a man, a young boy and a woman, and due to the location of the grave, the female remains are believed to be Estrid. From the beginning, there were theories that the boy could be Estrid’s first-born son Gag, who died in childhood. Still, thanks to DNA tests on both skeletons, they have been able to dismiss that theory.

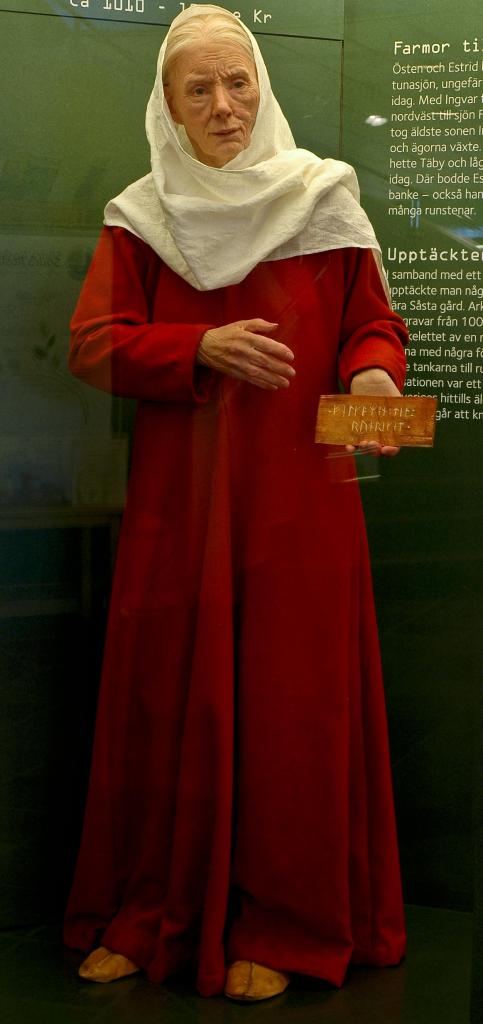

Estrid had been given a Christian burial, which has benefited posterity and archaeological research. It meant that she was buried as she was and not burned, which was usually the case during the Viking Age. She lay with her feet to the East in a hollowed-out log with grave goods consisting of a jewellery box containing two silver coins, three weights and a silver ring. Also placed next to her was a knife. When the skeleton was examined and put together, it turned out that Estrid had become crooked over the years. It was also noted that she had broken one of her arms at some point during her life. In addition, her teeth had been inflamed, and she possibly suffered from toothache durig the last period of her life.

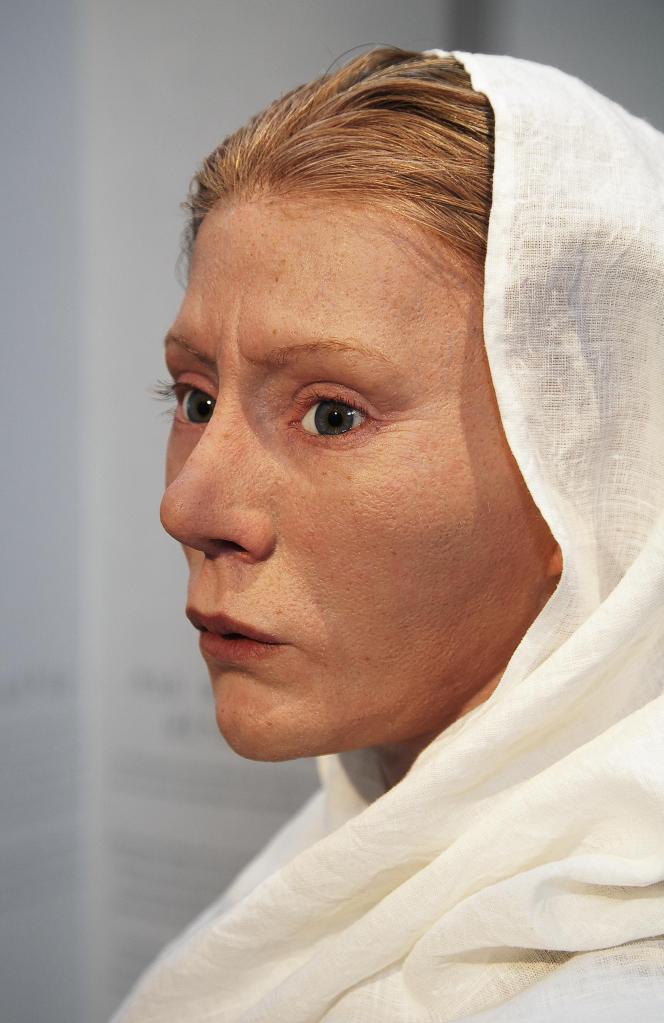

Now we also know what she may have looked like, thanks to the sculptor Oscar Nilsson, who recreated Estrid’s face as a child and at the age she was when she passed away.

Sources:

Stockholms Läns Museum

Täby kommun

Runriket

Images:

Rune stones from Creative Commons.

Images of Estrid Sigfastdotter used with kind permission of Stockholms Läns Museum

Photo of Young Estrid shot by Elisabeth Broogh.

Lämna en kommentar