In February 1306, Torgils Knutsson was executed by beheading on Pelarbacken, better known as Götgatsbacken in today’s Stockholm.

Despite opening with his death, he’s not the main character here.

Instead, it’s King Birger Magnusson – ward of Torgils Knutsson – and his brothers, Dukes Erik and Valdemar, all sons of King Magnus Ladulås and thus also grandsons of Earl Birger.

While both Earl Birger and Magnus Ladulås worked to strengthen peace in the country, domestic peace, court peace, church peace and women’s peace, there was no peace between the three brothers.

When Magnus Ladulås died on Visingsö in 1290 at about 50 years old and 15 years on the throne, he left three underage sons behind. Torgils Knutsson oversaw leading the interim government and leading young Birger on his path to eventually taking the throne.

While Birger became king, Erik and Valdemar had to settle for becoming dukes over Södermanland and Finland, respectively, something the two brothers found to be far from enough.

The absence of peace between the heirs of Magnus Ladulå resulted in Erik strengthening his power by forming alliances with powerful men. He was also married to the daughter of Norwegian king Haakon Magnusson, which didn’t hurt his cause. Valdemar, in turn, was married to a daughter of the loathed Torgils Knutsson, a marriage he made sure to have annulled as the conflicts between Erik and Valdemar on the one hand and Birger and the powerful Torgils on the other grew.

As a result of the ”noise” they were making, Erik and Valdemar were summoned by Torgils Knutsson in 1305 to sign a treaty that would end their conflict-seeking and attacks against the king’s regime as well as against Torgils himself. The treaty meant that they would cease all contacts with foreign countries – which were not unlikely aimed at building alliances with other regents and power players, stop their attacks on the king and Torgils Knutsson, obey the king and barred them from coming to court unless they were explicitly summoned.

As they perceived it, the two disadvantaged brothers signed the treaty at Kolsäter’s farm in Dalsland but didn’t intend to abide by it. Why King Birger and Torgils thought they would is somewhat of a mystery.

In the following months, however, some at least temporary peace seems to have settled between the three brothers, something that would affect Torgils Knutsson: before the year was over, the three had joined forces to arrest him, and this ended, as previously mentioned, with a beheading on Pelarbacken.

Life’s not a fairy tale, not today and not in the Middle Ages, and there is no ”happily ever after” ending to this story, no brothers who fell into each other’s arms after removing a man who caused conflict, and no peace.

It would pass only just over six months after Torgil’s execution in February 1306, before Erik and Valdemar yet again attacked their royal brother.

The primary source for these events is the so-called Erikskrönikan – the Erik Chronicle -written in knittel verse in the 1320s or 1330s, relatively close to the events it describes.

According to the chronicle, King Birger held a banquet in Håtuna and invited his brothers, who arrived with their entourage, as befitted gentlemen at the time.

During the evening, the retinues armed themselves, contrary to both the legislation that the brothers’ father had enacted regarding domestic peace and the treaty they had signed.

Birger Magnusson was arrested and held prisoner for two years, an event that has gone down in history as the ”Håtunaleken”, the Håtuna game. When Briger was imprisoned, Valdemar and Erik carved out large chunks of the kingdom for themselves, giving Erik the largest part. Despite this, Birger was still king when he was finally released due to lengthy negotiations. He was still king and had lands to rule over, but they were significantly reduced.

According to historian Mikael Nordgren, this duchy of Duke Erik is the only attempt at a feudal ”state” made in Sweden.

Despite what had happened, more than ten years of relative peace passed between the brothers, but if Erik and Valdemar thought Birger had an element of ”forgive and forget” in him, that was a monumental mistake.

In the fall of 1317, Valdemar passed through Nyköping while Birger had moved his court to Nyköpingshus. Valdemar was invited to a banquet and asked also to bring their brother Erik.

This would be the beginning of the end for all of them.

Valdemar arrived first, and had it not been for his reassurance that everything seemed fine, it’s possible that Erik probably never joined the celebration, but he did.

One would think, after the so-called Håtunaleken, that it should have raised all kinds of red flags for Erik and Valdemar when Birger announced that their respective armed retinues would not be housed at Nyköpingshus but would have to seek accommodation outside the city.

But without objection, they sent their men away.

What was it about these brothers that made them, despite all their experiences and their agendas, so willing to trust each other?

Was it actual sibling love that got lost in politics and self-interest? Because the willingness to trust is, in hindsight, completely incomprehensible.

Like Birger a little over ten years earlier, Erik and Valdemar would have reason to regret that trust.

According to the Chronicle of Erik, Valdemar and Erik were surprised by men with crossbows during the night between 10 and 11 December 1217. King Birger is said to have commented on this with, ”Do you remember Håtunaleken? I remember it all too well. This one isn’t going to get any better.”

It would get a lot worse.

Erik and Valdemar were kept prisoners in Nyköpinghus core house, which, as it happens, is one of the buildings of the weathered royal house that still exists today.

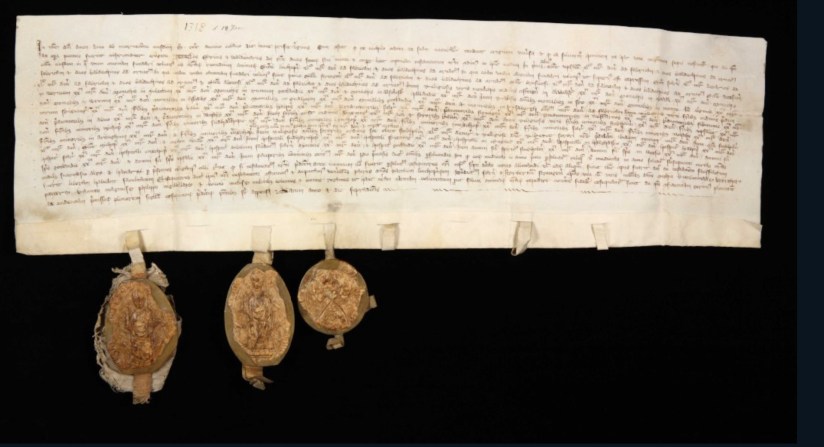

They never get out of here alive. Five weeks into their captivity, they write a joint will. We know that for sure because it still exists.

There, among other things, they instituted a canonicate – an office for a canon, which in turn was a member of a cathedral chapter – in Uppsala, Linköping and Skara cathedrals.

They also give money to a wide range of churches and monasteries, including Strängnäs, Västerås and Turku, as well as to the monks in Varnhem, Alvastra and Skänninge, alongside the nuns in Sko, Riseberga and Askeberga, among others. This, alongside gifts to a long list of other church institutions, was undoubtedly in a desperate ambition to save their souls. The gifts were to be secured by pledging their estates in Svartsjö, Algö and Hammarö.

And then they die. It’s unknown how, but according to legend, Birger let them starve to death.

We may never know if this was true.

But the fate of the two royal brothers has been said to be quite worthy of a drama by Shakespeare. Such a thing could also have existed if Sweden had a Shakespeare.

So, how did King Birger fare? Did he conquer both the land and the fortune without his brothers?

The answer can be summed up in a short ”No”.

Birger was not quite as popular a king as he had probably hoped. About six months after he imprisoned his brothers, the lawman (from the Swedish ”lagman”; someone who led the Thing and oversaw dealings within his juristiction) Birger Persson, who had been one of the witnesses to the brother’s will, led a rebellion against the king.

He chose to flee with his queen, first to Stegeborg castle in Östergötland, and when this fell into the hands of the rebels, on to Visby. They went to Zealand (Denmark), where King Birger lived for another four years. He and his queen are buried in Ringsted church.

Birger’s son was apprehended while trying to defend Nyköpinghus and executed in Stockholm in 1320. Instead, Duke Erik’s son Magnus was crowned king at the Mora stones outside Uppsala at just three years old. Magnus Eriksson would have a complicated reign, during which he was regularly vilified by none other than St Bridgid of Sweden.

Sources:

Sveriges Medeltid (Medieval Sweden) – Dick Harrison

Chronicle of Erik – author unknown

Swedish Diplomatarium – The National Archive

Images:

Swedish Diplomatarium – The National Archive

Creative Commons

Lämna en kommentar