When the wedding negotiations began for Cecilia Vasa and her future husband in 1564, she expressed that she would rather forgo marriage and instead become a lady-in-waiting to a monarch whom she had the most profound admiration for: Elizabeth I of England.

It was a wish not heeded; Cecilia became Margravine of Baden-Rodemarchen.

However, she had for several years exchanged letters with the English queen and also learned English to be able to move in English-speaking circles.

At last, the invitation from England came, delivered by a personal envoy. The journey began in the same year that Cecilia married, 1564. Besides Cecilia herself and her husband, Kristoffer II of Baden-Rodemarchen, there were 100 people, one of whom was Helena Snakenborg, who will get her own post on this blog and therefore will not be mentioned further in this one, who set out on an almost year-long journey.

Due to conflicts with Denmark, it was not considered safe to travel west via the Baltic Sea and thus pass the country. Instead, the journey went east and passed Reval in the Baltic, Poland, what was then called Prussia and the Spanish Netherlands.

In a 1565 writing, written by the Englishman James Bell to Queen Elizabeth and possibly ordered by Cecilia herself, the hardships of the journey and the places that were passed are told.

”And the XVIIIth daie of Septembre in the yeare of our Lorde God, 1564, Stockehollome (a cytie in Sweden where her brothers Courte is kepte) entringe a small vessell, beganne her iourney by water towardes a town called Tellinge;….”

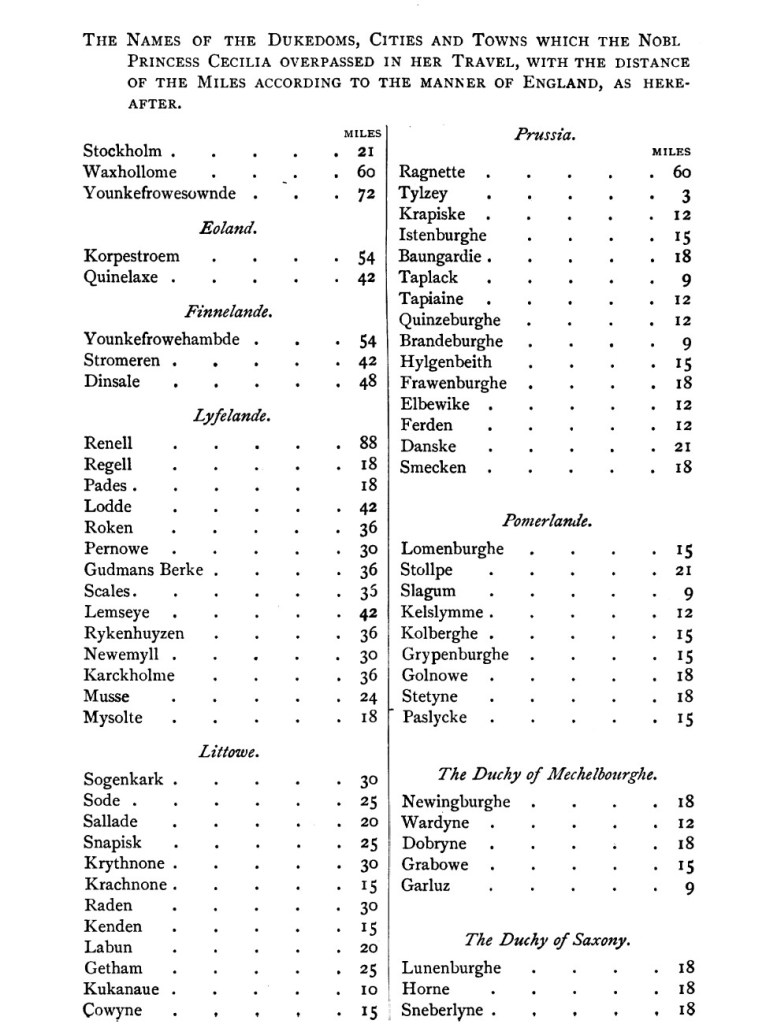

To underline the ordeal of the journey, James Bell has inserted a list of the fiefdoms, duchies, and places Cecilia and her entourage passed on their journey, including how far they travelled; this is available as a picture here in the post.

Without going into detail, it seems that some parts of the journey were more difficult than others. Among other things, James Bell expresses himself like this about what is possibly Lithuania and the city of Saločaì;

”…she departed from Mysse the XVIIIth of Marche ; and the XIXth came to Sallade in Lyttome, the moste barbarous countrey in the worlde : a people as rude of maners as frowarde of stomack : for whose uncyvill behavioure and uppelandishe fasshyones they are accoumpted Sadvage and brute beastes, even of their neereste neighboures.”

Regardless of the place described, Elizabeth either did not know it or did not like it. Otherwise, James Bell would never have expressed himself about it as he did.

But back to Cecilia’s journey: after she visited her sister Katarina in East Frisia, and according to some reports also at that time still imprisoned love Johan with whom she shared the memory of the Noise in Vadstena, she reached Calais early in September 1565, almost a years after the group left Stockholm.

James Bell often describes Cecilia as a heroine who undertook this journey, and it can be easy to forget that a trip through Europe in the 16th century was quite a different thing than making it today. Something that should also have been a source of both concern and tense anticipation for Cecilia and those who stood by her is that she becomes pregnant with her first child during the journey.

At a time when it was customary, at least among nobility and royalty, for the expectant mother to be isolated with her ladies-in-waiting in the weeks before childbirth and absolutely not to be disturbed, Cecilia travelled both by land and sea under conditions that were undoubtedly highly comfortable for her time, but which, to say the least, had left something to be desired in the present.

Perhaps it is Cecilia’s own concern or frustration that Bell expresses when he notes that it is common for a woman to go into isolation six to eight weeks before giving birth so as not to jeopardize the outcome.

But she who neither ”allowed herself to be insulted by her brother nor frightened by surging seas or surrounding rocks” would fight on and focus on the fact that the trip and the pregnancy were soon over.

And it almost coincided. Cecilia and her retinue arrived in London on 11 September 1565, and on 17 September her first child, a son, was born; Edward Fortunatus of Baden-Rodemachern.

By then, she had already had time to receive a visit from her great role model, Queen Elizabeth, at Bedford House, where she, her husband and son, together with their entourage, would live during their stay in London.

Edward was christened in the palace chapel at Westminster on 30 September and was carried to the christening by the Queen. The officiant was the Archbishop of Canterbury, who was assisted by three other bishops.

Elizabeth and Cecilia would get along well. Just the fact that Cecilia was allowed to take communion directly after the Queen at Christmas 1565 shows this. Not least, the Spanish Ambassador da Silva confirms this impression in his letters home. Queen Elizabeth and Cecilia attended parties and weddings together, as well as having dinners together.

Not entirely unexpectedly, Cecilia was tasked with convincing Elizabeth to marry Cecilia’s brother, Eric XIV. She reportedly turned to the Earl of Leicester, Robert Dudley, to find an ally in this endeavour. He was not the best choice for this, as he had plans for Elizabeth. As we know, all failed with similar ambitions.

Cecilia would also recruit British privateers for raids against the Danish, German and Polish ships. She had also not let go of the plans to free Johan and turned to Elizabeth for help with this.

There was just one problem: money. Gustav Vasa is often portrayed as the people’s king, but his court was one of the most opulent in Sweden, and Cecilia grew up in this environment. Even if that hadn’t been the case, balancing a budget and making sure the money was enough wasn’t easy for her.

Being part of Queen Elizabeth’s court cost money, and to cover the costs, Cecilia and her husband—whose kingdom certainly did not rely on large financial assets—borrowed money where they could, mainly from George North and John Dymond but also from the doctor Cornelius Aletanus. This very last contact became one of the first nails in the coffin for the relationship between Cecilia and Elizabeth. Namely, Aletanus was out of favour with the Queen after he failed to produce gold at her request.

But it was not only the financial situation that caused Cecilia’s position at the English court to waver but also her close contacts with the Spanish ambassador, who, among other things, ignored the fact that parts of the Countship of Baden-Rodemachern were within Spanish Luxembourg.

During the spring, Cecilia’s husband had gone home to Baden-Rodemachern to raise money. The situation had become untenable; in the streets, creditors yelled obscenities at the couple as they traveled to court, and once there, plays were staged mocking the princess’s financial situation. The stay in England was turning into a nightmare.

The plan was for Kristoffer to return in disguise, which he did, and take his similarly disguised wife and theirs out of the country.

It didn’t work out at all, and Kristoffer was arrested and put in the debtor’s house – another humiliation – and stayed there until Elizabeth forced German merchants to pay bail for him. It was time to go home.

Even this enterprise was not without pain: in Dover, creditors caught up with the party and took what was of value, not only from Kristoffer and Cecilia but also from her ladies-in-waiting. Cecilia considered herself robbed, and when the son she was expecting was born paralyzed, she blamed this event.

A further consequence was that England became legitimate prey when Cecilia later embarked on piracy.

Sources:

A Narrative of the Journey of Cecilia, Princess of Sweden, to the Court of Queen Elizabeth – James Bell, 1565. (Transcribed by Miss Margaret Morison, Royal Historical Society, April 21, 1898)

Vasadöttrarna – Karin Tegenborg Falkdalen (The Vasa Daughters)

Om prinsessan Cecilia Wasa, markgrefvinna af Baden-Rodemachern. Anteckningar.- Fridolf Ödberg, 1896. (About the Princess Cecilia Wasa, Margravinne of Baden-Rodemachern. Notes.)

Cecilia – Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon – Georg Landberg, 1927.

Images:

Creative Commons

Lämna en kommentar