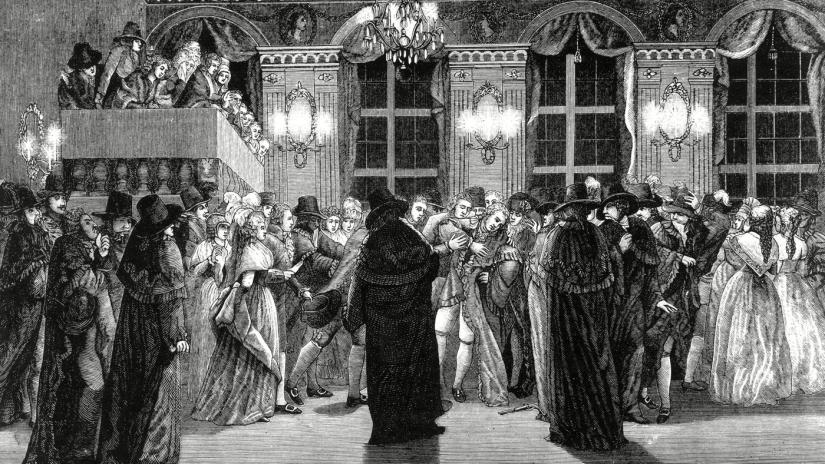

On Friday, March 16, 1792, Gustav III held a public masquerade ball at the Stockholm Opera House, and it did not end as he had planned. Instead, it was an evening that developed into one of the most dramatic events in Swedish history.

The background was Gustav III’s war against Russia, and not least the handling of the so-called Anjala men, a group of officers who had opposed the king’s war policy. The officers had conspired to end the war by negotiating with Russia and had, with that aim, sent a ”note”, a diplomatic message, to Catherine II of Russia, in which they declared their dissatisfaction with the war, that it was against the interests of the Swedish nation and that they wanted peace. Not entirely unexpectedly, Gustav III saw this as treason. The leaders of the conspiracy, Carl Gustaf Armfeldt, Johan Anders Jägerhorn and Johan Henrik Hästesko, were arrested, and the latter was executed in 1790.

Nor did the introduction of the Act of Union and Security or the king’s actions during the Riksdag in 1789 improve things. The Act expanded the king’s power and removed most of the nobility’s privileges, while commoners could now hold most offices in the country and buy freehold land. This gnawed at the Swedish nobility.

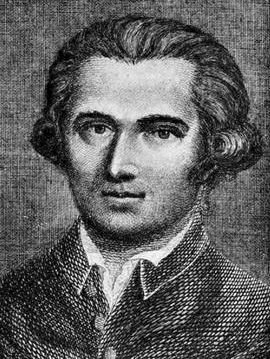

The conspiracy began to take shape during the winter of 1791–1792, most likely under the leadership of the German general and baron Carl Fredrik Pechlin. Pechlin had come to Sweden as a six-year-old with his father, Johann Pechlin, who was stationed in Stockholm as the Holstein minister. Carl Fredrik became a naturalized Swedish nobleman in 1751, the same year he became a lieutenant colonel in the Kalmar regiment. He was prominent during the so-called Freedom Period (1719 – 1772 ).

The participants in the conspiracy met at Pechlin’s home on Blasieholmen, where Pechlin, together with Jacob and Johan von Engeström, Carl Pontus Lilliehorn, and Johan Ture Bielke, sketched out the constitutional plans for a Sweden without Gustav III. The revolutionary part of the nobility was prepared to reap the benefits that they expected to come from the king’s removal but was not willing to engage in an actual regicide.

Instead, that part of the conspiracy was handed over to Jacob Johan Anckarström, Adolph Ribbing and Claes Fredrik Horn. The extent to which the assassination plans were well-known to those who opposed Gustav III’s rule is unclear. Anckarström’s hatred of the king was also personally motivated; he had been almost ruined by the king’s policies, and when the time came to write a confession, he called Gustav III ”a perjurer and a perpetrator of violence”.

Even before the ultimately fatal shot was fired there at the opera, Anckarström, Horn, and Ribbing had already set out several times to kill the king. As early as the beginning of 1792, Anckarström and Horn made their way to Gustav’s window at Haga Castle, looked in, and were horrified.

What they experienced was an already dying king sitting on a sofa surrounded by books with a face like that of a dead man. The sight made them flee back to their horses and set off. Possibly, they hoped that the king would leave this world soon without their assistance. However, that was not to be.

They also had plans for Anckarström to shoot him at the theatre, and together with Ribbing, he also followed the king to the Parliamentary meeting in Gävle, the last Gustav III would attend, but the ”right” opportunity to kill a king never presented itself.

After the plans to overthrow Gustav in Gävle failed, the idea of striking at a public masquerade ball at the opera was born. The first date decided upon was March 2, which proved impossible, and then March 9. That day was mercilessly cold, and only a few people came to the ball, which made it more difficult to act hidden from other guests.

The next opportunity came on March 16. Since this was most likely the last public masquerade ball of the season, it was felt sure that the king would attend, which was not always the case. When Ribbing informed Pechlin of what was going on, the latter claimed that he had the opportunity to gather several regiments in Stockholm that could assist in carrying out the hoped-for revolution.

When the day of the assassination arrived, some of the members of the conspiracy gathered at Pechlin’s house to make plans for what would happen when the king was no longer alive. For their part, Anckarström, Ribbing and Horn decided that all three would attend the masquerade ball, and Anckarström then went home to get weapons. In addition to a butcher’s knife, he took with him two pistols loaded with bullets, shotgun pellets and nail heads. Last but not least, he and Horn dressed in black cloaks and white masks and headed for the opera.

For his part, the king began the evening with a supper at the Opera, which was a different Opera than the one that exists today. The banquet was held upstairs in the house, in the so-called Drabant Hall of the Royal Apartment. It was accompanied by Gustav III’s master of the stables, Hans Henric von Essen, captain on duty Gustaf Löwenhielm, chamberlains George de Besche and Carl Borgenstierna, and lieutenant Fredrik Gustaf Stiernblad.

Towards the end of the banquet, something happened that could have given this story a completely different ending. Just as the company had begun to wrap up the whole thing and get ready to join the masquerade downstairs, chamberlain Carl Magnus Tigerstedt handed the king a letter written in French.

It was a warning from one of the conspiracy members, Carl Pontus Lilliehorn, who anonymously announced plans for an attack on the king. Gustav III is said to have shown the letter to Hans Henric von Essen, who was deeply horrified and, not unexpectedly, urged the king to refrain from attending the masquerade ball.

Gustav did not want to hear anything like that: “Let them think that I am afraid?” he asked his master of the stables, who then instead asked him to wear a cuirass as protection against what might happen. The king wouldn’t hear of this either.

Instead, he stood, fully visible to the masquerade participants, in a window with an overview of the festivities below. He noted that whoever it was had now had the opportunity to shoot him if they wanted and that the masquerade seemed pleasant. Arm in arm with von Essen, he descended the stairs to join the ball.

It had been just before midnight when the supper ended and just after midnight when he spoke with Captain Carl Fredrik Pollet, who had been on his way home but was stopped by the king and was obliged by etiquette to accompany him towards the wings.

When he was side by side with them, Gustav III was surrounded by men in black cloaks and white masks: Anckarström and Horn.

Von Essen would later testify that the crowd had forced him to walk just in front of the king, but still arm in arm with him, to make his way through the groups of guests and that when they were a short distance from the hall where the ball was taking place, a shot was heard. Walking behind the two, Pollet saw the king start and shout, “Aj, aj Je suis blessé” – I have been wounded.

Immediately after the shot was fired, several people began shouting that the fire was loose, probably members of the conspiracy who wanted to create confusion. Still, the fact was also that the king’s masquerade costume had caught fire from Anckarström’s shot.

The king was taken back to the palace by a bumpy and painful carriage ride but is said to have been in good spirits when he arrived and thanked everyone present for their help.

At the opera, a ring was formed around the remaining guests, and everyone had to unmask themselves and have their names written down before they were allowed to leave the premises. Even before this, Carl Fredrik Horn had managed to escape, but Ribbing and Anckarström remained, and the latter hid one of the pistols by the stairs.

Things had not gone as they had planned. The intention had been for the king to fall dead on the spot and chaos to break out.

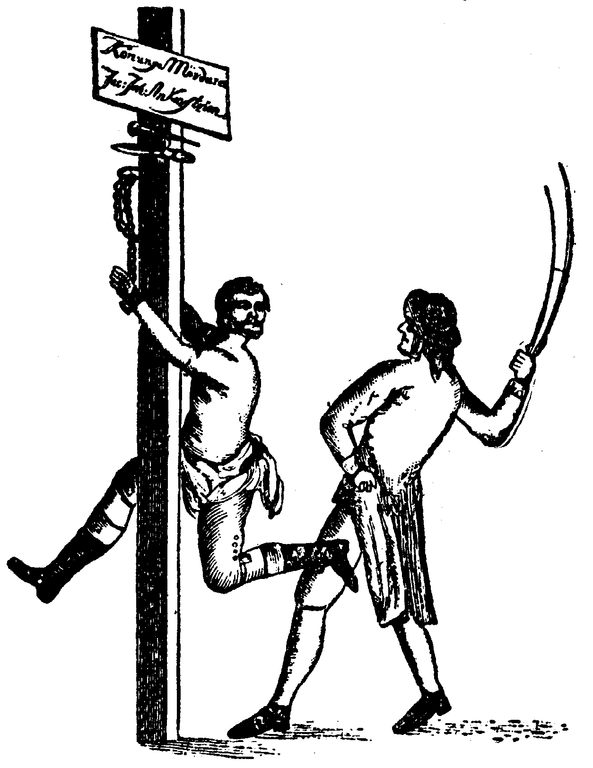

Now, instead, the king was still alive, and Anckarström was arrested the morning after the shot was fired. He confessed at the first interrogation but refused to say whether anyone else knew about the murder plans. When asked who he had been meeting with recently, he mentioned Ribbing and Horn, who were also arrested.

During the investigation, more noble names appeared among those suspected of having been on the fringes of the conspiracy. When the investigation led to the king’s own brother, later Karl XIII, police chief Nils Henric Liljensparre closed the investigation. But there was no doubt that hatred for Gustav III ran deep among the nobility.

It would take Gustav III almost two weeks to die, which happened on March 29. Just under a month later, Jacob Johan Anckarström was executed, while Ribbing and Horn were exiled for life.

Gustav III was followed on the throne by his son Gustav Adolf, Gustav IV Adolf, in the regency succession, whose life ended tragically in a different way.

Sources:

Gustav III: en biografi – Beth Hennings

Historien om Sverige. Gustavs dagar – Herman Lindqvist

Ekot av ett skott: [öden kring 1792] – Alf Henriksson

Gustav III – Riksarkivet

Lämna en kommentar