Imagine that, for whatever reason, you are out walking on a bog, and suddenly you see what appears to be human remains. A hand sticks up, or maybe even a face looks back at you from between the tufts.

It could, of course, be a modern-day crime victim. But that is often not the case. Moss corpses are a speciality of northern Europe, and this blog post will focus on the Scandinavian instances, along with some of their macabre cousins: the wetland skeletons.

However, first, the moss corpses: these are preserved due to the specific chemical composition and environmental conditions of the bog. These include low pH, lack of oxygen, and the presence of tannic acids, all of which help to inhibit the decomposition processes and preserve bodies, sometimes even soft parts such as skin and hair, for a long time.

There are many different explanations for the fact that human remains have ended up in bogs. Sometimes it has been about sacrificial sites, such as Skedemosse on Öland, which are believed to have functioned in this capacity for over a thousand years in some cases. In this heat wave that is prevailing in Scandinavia in mid-July 2025, however, we will focus on a few individual cases.

With a slight Swedish bias, we will start with the Bockstens Man. It was the 11-year-old Thure Johansson who, in 1936, together with his sister Gulli, helped harrow the Bockstens bog for peat when they found what they thought was a straw doll.

It was not, as it turned out. What the children had come across was a 700-year-old murder victim. However, it would take a few years before they realised that he was a murder victim.

For a long time, researchers claimed that nothing could be said about the Bockstens Man – we don’t have any other name – but when casts of his skull were carefully examined in the 2000s, it became clear that he had died from at least three blows to the head. It was Professor Claes Lauritzen, then head of the craniofacial unit at Sahlgrenska Hospital, who got his hands on the cast in 2006 and was able to quickly determine that the Bockstens Man had received a blow to the lower jaw, then one to the right ear and then a fatal blow to the back of the head.

The Bocksten Man was also impaled, something that could be done in a superstitious time as an assurance that the dead person would not walk again. According to older sources, such as the legend, impalement was something that was done collectively after someone was executed, and those who were affected were considered evil people. Either those who abused power were serious criminals, perhaps murderers themselves, or were skilled in witchcraft. Another category is those who committed suicide, and that is the category we can be reasonably sure that the Bockstens Man did not belong to.

So who was he? We will probably never know. What we do know is that he was well-dressed.

The Bocksten Man was equipped with not only a substantial head of still red, curly hair, but also a suit of clothes that is today the best-preserved set of clothes from the 14th century.

The clothes he wore are made of woven wool that has been waxed or pounded into vadmal, a type of wool fabric that is warm and resistant to rain. The width and quality of the fabric suggest that it was home-woven, possibly by his wife or by servants.

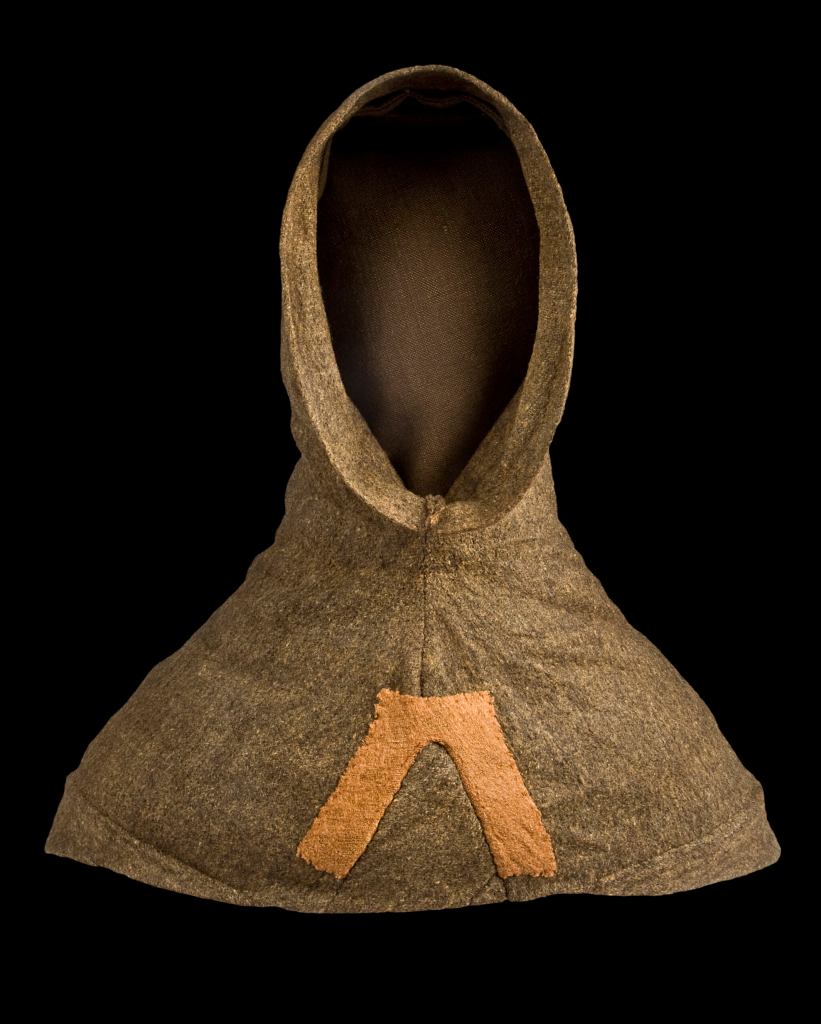

Among the garments he was wearing when he lost his life is a cone cap, which is said to be the most characteristic garment of the time he lived in. As the name suggests, it was a cap, or hat, shaped like a cone. While it was on the head, the cone itself could be wrapped like a scarf. This can be understood as meaning that he died during the cooler part of the year; no one needs a scarf in the middle of summer.

Instead of trousers, he wore what were called hoses, a type of stockings used at the time, and which were held up by leather straps which in turn were attached to a belt around the waist, under the tunic he also wore. The tunic was a basic garment of the Middle Ages, and on top of this, he wore a belt to which two knives were attached, along with a leather object, probably a small bag.

Over his trousers and skirt, he wore a cloak, which left an opening for his right arm. Apart from making it easier to carry things, the design was also intended to allow for quick access to the sword or knives worn on his left hip in a threatening situation, which was not uncommon at the time, unlike if he were left-handed. Still, in the Bockstensmannen’s case, the knives remained in his belt.

On his feet, he had so-called footmuffs, which consisted of recycled garments that were wrapped around his feet to keep out the cold. In the Bockstensmannen’s case, these had felted and become like slippers. In addition to these, he wore leather shoes with flat soles.

The clothes the Bockstensmannen wore indicate that he belonged to the upper class, and suggestions have been made that he may have been a scribe, a bailiff or even a priest. His clothes have also contributed to increased knowledge of how people dressed in the late 14th century, and the garments are among the best-preserved from this time found in Europe.

In connection with the repair and casting of the Bockstensman’s skull, work also began on giving him a face, a task carried out by the archaeologist and artist Oscar Nilsson, who has also given faces to, among many others, Earl Birger, the Barum Woman and the crew of the royal ship Kronan.

Tollund Man is another bog body found in Scandinavia, this time in Jutland, Denmark. Here, too, the discovery was made in connection with peat extraction on May 6, 1950. But while Bockstens Man lived during the Middle Ages, Tollund Man is much older than that. He was hanged sometime around 400 BC Later research has changed the date of his death from between 400 BC and 200 BC to sometime between 405 and 384 BC.

He was between 30 and 40 years old at the time, and had short-cut hair. Just like Bockstens Man, he is now red-haired, but in both cases, this is due to the conditions in the bog. DNA tests on Bockstens Man have shown that his hair was originally dark. As for Tollund Man’s clothing, assumptions have had to be made. He wore a pointed cap on his head and also wore a belt. He also wore a yellow garment, believed to have been made of linen. The soles of his feet show signs that he was used to walking barefoot. Just like his murder, it is impossible to know what the Tollund Man did to deserve to be executed; possibly, or perhaps even likely, it was a ritual human sacrifice.

This theory may be confirmed by the fact that 12 years earlier, just ten meters from where Tollund Man was later found, the remains of a woman, the Elling woman, were found. She had also been hanged, but a couple of hundred years after Tollund Man. Her remains had not been preserved as well, and at first it was thought that they were the remains of an animal. It was then discovered that she was wearing a woven wool belt. Further examination revealed that she was also wearing a knee-length sheepskin coat and cowhide leggings. Her hair was tied in an elaborate, 90-centimetre-long braid, and she was around 30 years old when she died.

In connection with the discovery of Tollund Man, an X-ray examination was performed, revealing that all of his internal organs were remarkably well-preserved. Among other things, it could be seen that he had eaten a last meal consisting of porridge or gruel between 12 and 24 hours before the execution.

When Tollund Man was first discovered, he was divided into several parts, as it was considered essential to preserve the head above all else. However, his body parts have been slowly brought back to him, most recently a big toe. The big toe had been left with the conservator who worked on Tollund Man in the 1950s, and one theory is that he cut off a toe to see how the conservation held up.

In the spring of 2024, his head underwent a second micro-CT scan, but the results have not yet been presented.

No remains like those of Bockstens Man, Tollund Man, or Elling Woman have been found in Norway. However, similar findings have been made in Germany, Poland, England and Ireland.

The Bocksten Man can be seen at Varbergs Fästning (Fortress), while the Tollund Man as well as Elling Woman is at Silkeborg museum i Denmark.

Sources:

Källor:

Mosslik och kärrskelett – Markus Eklund, Kandidatuppsats, Stockholms universitet FULLTEXT01.pdf

Begravning i våtmark pågick under årtusenden | Göteborgs universitet

Bockstensmannen – ett unikt fynd – Hallands Kulturhistoriska Museum

Vem var mannen i mossen – Kristina Ekero Eriksson/Populär Historia/2006

Ny teknik har givet Tollundmanden mere præcis dødsattest – Jyllands-Posten

All photos related to the Bocksten Man: Charlotta Sandelin/Halland Cultural History Museum

Lämna en kommentar