Birger jarl is a name that most Swedes recognise; even if it’s the only thing you know about Swedish history, you likely know this: there once was a man called Birger jarl. Except he wasn’t—that was his title, akin to the English earl. His actual name was Birger Magnusson, and he was born around 1210 at the Bjälbo estate in Östergötland.

Birger dominated many historical accounts to the extent that even if you know ”jarl” is a title and not a surname, you might still think he was the only one. But that is not the case. He was actually the last jarl of the Swedish Middle Ages, and upon his death, the title also ceased to exist. Before this happened, a great deal took place.

Birger was the son of a woman whose life has already been told on this blog, Ingrid Ylva, and her husband, Magnus Minnesköld. As such, Birger was part of the extremely powerful and influential Bjälbo family in the 13th century, later referred to in historiography as the Folkunga family.

Around the time of Birger’s birth, his father died, leaving Ingrid Ylva a single mother of three sons for an undetermined period, before she likely remarried someone forgotten by history.

Birger himself got married when he was about 25 years old, to Ingeborg Eriksdotter, the sister of the reigning king at the time, Erik Läspe och Halte (translated as “Eric Lisp and Limp” in English). It is assumed, much like the Roman emperor Claudius, that Erik had both a speech impediment and a limp.

Together they had eight children, two of whom became kings: Valdemar and Magnus—the latter remembered as Magnus Ladulås. This family connection set the stage for the turbulent politics that followed.

The Swedish early Middle Ages were marked by instability, with kings frequently being deposed and restored. Erik Eriksson, also called Läspe och Halte, was elected king at six, meaning that a council of bishops and nobles, including Knut Holmgersson (Knut Långe, possibly “The Tall”), ruled in his place. Knut aspired to the throne and, after the Battle of Olustra in 1229, overthrew the 13-year-old Erik. Knut Holmgersson, a member of the Folkungs—distinct from the Folkunga family—did not reign long. He died five years later, and Erik returned to the throne, though true power lay with the earl and Folkung Ulf Fase.

Ulf Fase disappeared sometime around 1247–1248, possibly dying in the Battle of Sparrsätra in 1247 when his troops met King Erik and Birger Magnusson and lost. Another possibility is that he was captured and executed. After this, Birger Magnusson was given the title ‘jarl,’ which has often been mistaken for a surname.

The title jarl, as previously mentioned, has its equivalent in the English earl, and existed in Scandinavia from the Viking Age into the early Middle Ages. However, it was not a title for the common people; with it came numerous official responsibilities.

The person who held this position was the king’s highest official, responsible for both military and administrative duties. Before he received his title, Birger Magnusson had already proven himself as a soldier. He led what is referred to as the ”Second Crusade” against the Tatars in Finland and took part in the 1240 Battle of the Neva against Russian troops led by Prince Alexander of Novgorod. During this battle, Alexander earned the name Alexander Nevsky, becoming a significant figure in Russian and Soviet historiography.

For Birger, this would mean that he would, in practice, lead the country until his death. Notably, already during his first year as earl, in 1248, he was present at the Skänninge meeting—a gathering in Skänninge aimed at regulating church practice in Sweden.

The Pope, Innocent IV, was somewhat provoked by the Swedes’ inability to establish themselves in the European Catholic community. Not only had the Swedes, and especially the Svear, located in the region around Mälaren and Uppsala, been more reluctant to be Christianians than the rest of Scandinavia, not to mention the rest of Europe. It was also more the rule than the exception that Catholic priests and bishops in Sweden had families.

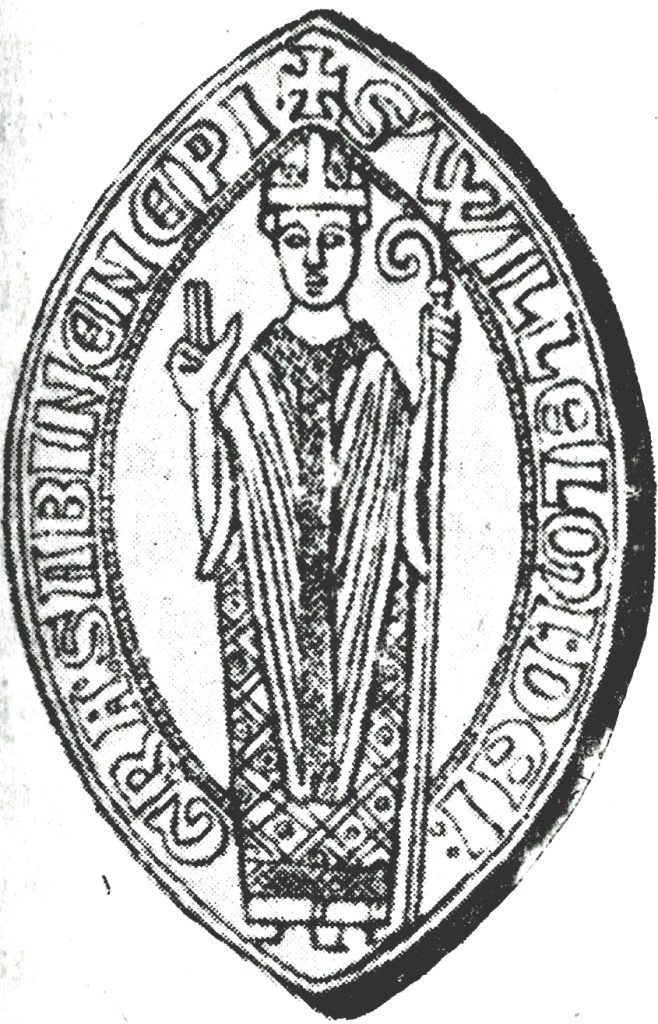

The fact is that at this time in Sweden, it was extremely common for those who became priests to have a father who was also a priest. That was clearly not allowed within the Catholic faith. So, now the Pope had sent his legate, William of Sabina, to Sweden to settle the score with the unruly clergy. As mentioned, Birger jarl was also present.

This particular issue was rectified by allowing those who were married to continue to be married, those who lived and had children with someone without being married, usually the housekeeper, to live in celibacy, and by strictly forbidding this practice. It should be said here that, despite all of William of Sabina’s papally sanctioned pointers, it took about a century before this idea of a life of celibacy, although not fully, caught on among the country’s priests and bishops.

The meeting also meant that Birger jarl received the right to introduce Roman law in Sweden. Roman law may sound suspicious, but in practice it is just the system on which our laws are based.

Birger would also enact many laws during the rest of his life, but we should not get ahead of ourselves. At the time of the Skänninge meeting, Birger Magnusson was already a highly influential figure; nevertheless, even more power would ultimately fall into his hands.

On February 2, 1250, Erik Läspe and Halte died at the age of 34, marking the end of the so-called Erikska dynasty. Meanwhile, Birger was in Finland on another crusade, where he helped found Hämeenlinna Castle.

When he returned home, his eldest, but only ten-year-old, son, Valdemar, was elected king. This decision was not entirely illogical, as Valdemar was the nephew of the recently deceased childless king and the son of the man who, alongside the king, had been Sweden’s most powerful figure—Birger himself.

The fact that Valdemar was underage meant, in practice, that Birger now became the regent of Sweden, despite the lack of a coronation and a royal crown.

The change of power was, of course, not peaceful. This was unsurprising, given that Sweden did not experience orderly transitions at this point in history.

In the Battle of Herrevadsbro in 1251, Birger jarl and his forces defeated rebel forces, reinforced with probably German mercenaries, and thus his son, and above all Birger himself, sat relatively securely on the country’s throne. Around the same time, Birger jarl is said, at least according to the Chronicle of Erik, to have founded Stockholm.

.It is also possible that there is room to question this claim. But the fact remains: the oldest preserved mention of ”Stokholm” is signed by Birger and Valdemar.

The letter of protection for the nuns at Fogdö Monastery, later known as Vårfruberga, states that Valdemar and Birger take the nuns and all their possessions and provisions under their protection, exempting them from all forms of taxation. This letter is signed in July 1252.

Birger also aimed to increase Sweden’s revenue by seeking to attract German merchants, who were exempted from trade taxes and duties. He allowed these merchants to settle in Sweden with the same rights as existing residents. Birger intended for German merchants to teach the Swedes how to grind grindstones, and as a result, Germans soon dominated certain Swedish towns.

We learn about Magnus Ladulås’s protective laws in elementary school. But they weren’t really his. Just a development of Birger jarl’s protective laws. It was Birger who instituted the Women’s Peace Act, which meant that women were not allowed to be raped or kidnapped. You might be a little surprised today that such a law was even needed, but as someone once said, ”history is a different country. They did things differently there.” He also instituted the house peace, which essentially meant that one should be safe in their home; the church peace, which meant no violence in the church; and the court peace, which, in today’s terms, means that our decision-making bodies should be able to meet without external or internal threats.

If you think that Birger jarl’s Women’s Freedom Act is a bit basic, you should know that he was behind another important change in the law for the benefit of women. This was a time when women were entitled to absolutely nothing when their parents passed away. However, Birger’s legislation would have required a daughter to inherit at least half of what a son received when parents with assets passed away.

Today, it may sound absurd, but in the 13th century, it was a significant and important change in terms of women’s ability to have their own agency and protection. This change in the law remained in effect until 1845, when daughters were granted the same inheritance rights as sons. In addition, Birger jarl also abolished the “iron burden,” which was, in short, a process where a person accused of a crime could prove their innocence through divine intervention.

It is reasonable to assume that divine interventions were rare and wrong convictions were commonplace. With this reform, Sweden inched closer to becoming a true society of laws.

When Valdemar came of age, Birger continued as regent at his side, and this relationship lasted until Birger Magnusson’s death on 21 October 1266, at the age of approximately 56. He became not only the last jarl of Sweden, but also the last Swedish regent – albeit uncrowned – mentioned in the Icelandic sagas.

Birger Magnusson was buried in Varnhem Church alongside his second wife, Mechtild, daughter of the German Count Adolf IV of Holstein and queen dowager after the extremely short-lived Danish monarch Abel, who reigned from 1250 to 1252.

When Stockholm City Hall was completed in 1923, the decision-makers in Stockholm had intended that Birger, as the founder of Stockholm, would have his remains moved there. However, the Varnhem Church Council said a firm “No”, and Birger remained where he was.

Despite all the peace laws he had instituted, there would be no peace between Earl Birger’s descendants. Nine years after Birger’s death, Magnus Ladulås – a surname he did not have – overthrew his brother Valdemar and seized the throne. Magnus’ own sons would later be involved in Håtunaleken and Nyköpings Gästabud. None of this, however, affects the influence that Birger jarl had on the development of Sweden for many centuries.

Sources:

Jarlens Sekel – Dick Harrison

Birger Jarl – Jarlen som byggde riket – Dick Harrisson

Svenskt Diplomatarium – Riksarkivet

Birger Magnusson – Sten Engström/Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon

Holmger Knutsson – Hans Gillingstam/Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon

Knut Långe – Hans Gillingstam/Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon

Svitjods undergång och Sveriges födelse – Henrik Lindström, Fredrik Lindström

Lämna en kommentar