The connection between the witch trials in Salem, USA – those that have been the subject of at least one horror film – and Sweden may not be obvious, but they are there. It started in Mora in Dalarna.

The process, which also included the region of Älvdalen, also in Dalarna, was part of the mass hysteria that spread in Sweden between 1668 and 1673 during the reign of Charles XI. It has gone down in history as the Great Noise.

The mass hysteria, which would end with 300 lives lost, began with the 11-year-old Gertrud Svensdotter from Älvdalen, who was alleged by a boy to have walked on water when they herded goats.

In what one can assume was pure self-preservation, Gertrud herself, when interrogated by the priest, accused the maid Märet Jonsdotter, whom she most likely had gotten to know when she, Gertrud, lived with her parents in the county of Härjedalen which shares a border with Dalarna.

Gertrud claimed that Märet had taken her to a crossroads when she was eight years old. Once there, she called on Satan, who appeared in the form of a priest. This would only have been the beginning of a period of travels to Blåkulla, where witches according to Swedish lore celebrate sabbath together with the devil, when they, with the help of magical ointments, used both cows and Gertrud’s father as a means of transport to get to the witch sabbath.

Gertrud’s accusations were like pulling the cork out of a bottle. Suddenly, child witnesses – because those who accused neighbors, siblings, and often parents of witchcraft in the coming years were, in most cases, children – appeared from all directions. While children usually had little say in 17th-century Sweden, these testimonies were seen as the absolute truth.

As a consequence of these first accusations, seven people died in Älvdalen on May 19 1669. They were Knopar Elin Knutsdotter, 70 years old, Bland-Anna, 70 years old, Lasse Persson, 20 years old, Bond Elin, 40 years old, a woman whose name did not survive history, as well as Gålich’s Anna Olsdotter, 17 years old and Brita Andersdotter, also 17 years old. Out of them, four had been convicted based entirely on children’s testimonies about how they had been taken to Blåkulla. The other three confessed after various forms of torture.

The hysteria spread to Mora, and on August 12, 1669, the newly formed Dalarna Witchcraft Commission arrived, marking the start of the witch trials. Both children and adults were questioned, and it was clear that whether this Commission believed in the accusations levelled against individuals depended on the individual’s previous reputation. In other words, according to the Commission, it was more believable that an old woman, maybe knowledgeable in herbs and the art of healing, was a witch than a similarly accused sergeant.

In Mora, 23 out of 60 people accused of witchcraft died. They were mainly women, except one man who was also executed. In age, they ranged from 25 to 79 years. But even if the witch hysteria raged on through the villages, it could have been much worse if it had not been for the justice Anders Stiernhök. In time, he became director of the Witchcraft Commission, and it is clear that he did not give much credence to the children’s testimony. Preserved documents show that he questioned claims, saw through contradictory stories, and asked both control questions and counter-questions. It can be stated that while people were accused of witchcraft also in Rättvik, no one died there as a result of the children’s claims. Perhaps it was the influence of Anders Stiernhöök and his father, who was also deeply sceptical of the idea that there were witches who took children to Blåkulla, that made the witch trials of Mora a lesser tragedy than it might have been.

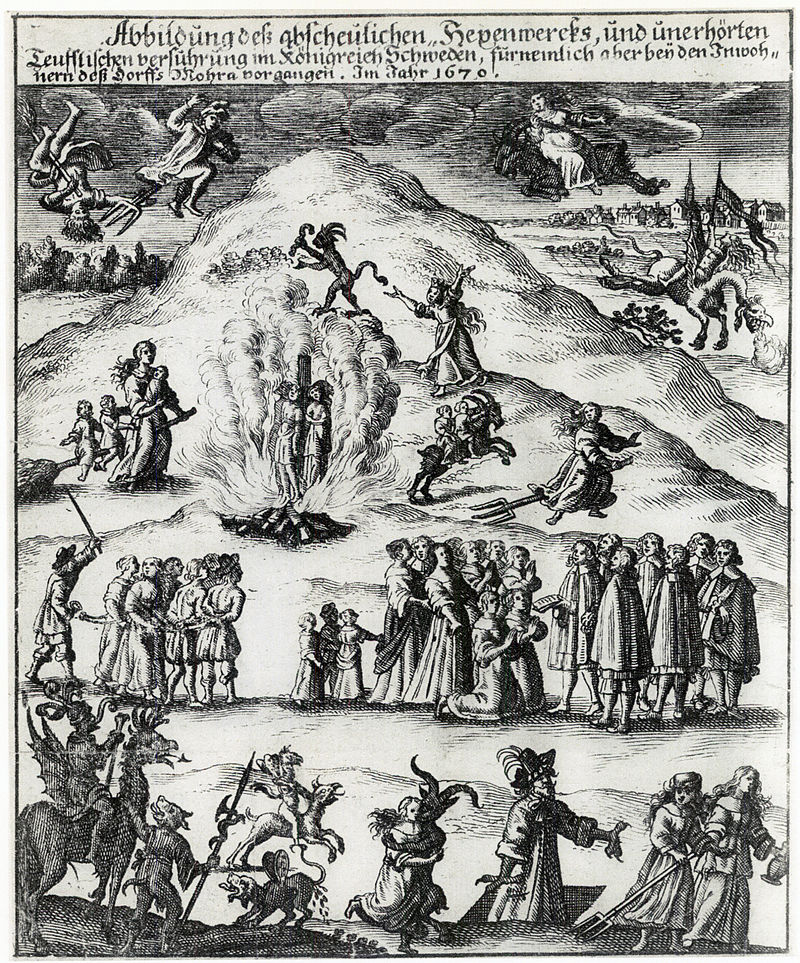

But what about the connection between Mora and Salem in the USA? Well, in Germany an engraver whose name has been lost to history heard the news from Mora. He illustrated the events as he thought they happened and then made a copper engraving of people burning at the stake. This provocative image is widely believed to have inspired the witch trials in Salem, Massachusetts. It should be pointed out, however, that neither in Sweden nor the United States was anyone alive burned at the stake. However, it was common in the unknown illustrator’s homeland, Germany.

Sources:

Lagerlöf-Génetay, Birgitta. De svenska häxprocessernas utbrottsskede 1668-1671. Stockholm: Akademitryck AB, 1990

Guillou, Jan, Häxornas försvarare, Piratförlaget 2002

Åberg, Alf, Häxorna: de stora trolldomsprocesserna i Sverige 1668-1676, Esselte studium/Akademiförl., Göteborg, 1989

Östborn, Andreas (red.), Dalarnas häxprocesser, Stift. Bonäs bygdegård, Mora, 2000

Lämna ett svar till Superstitions That Once Consumed Entire Cultures Avbryt svar